Introduction

Much of the contemporary AI risk discourse focuses on large-scale existential threats to the human species. However, there are more mundane risks that are also worth considering, one of which is the possibility that AI could enable a new wave of totalitarianism.

Background

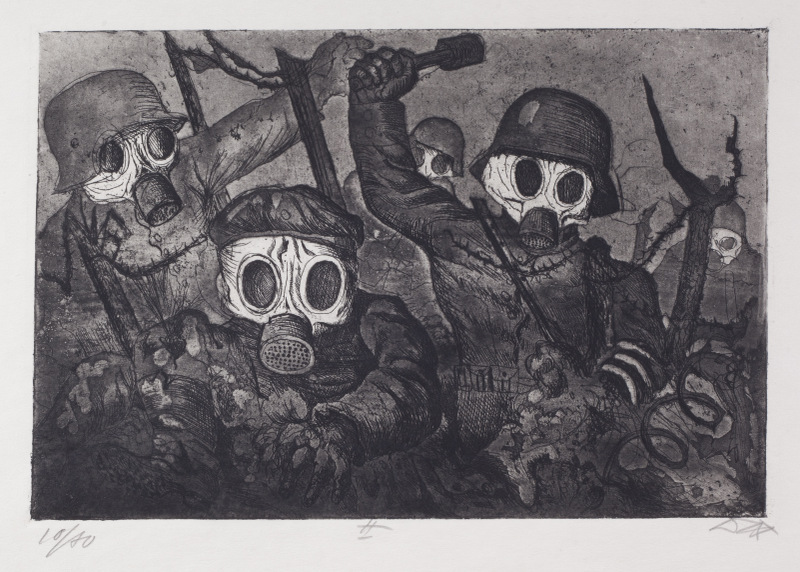

Throughout history, advances in communication and bureaucratic technology have enabled larger and more powerful states, with increased ability to monitor and control their populations. In particular, the first half of the twentieth century saw the rise of totalitarian regimes that used new technologies to achieve unprecedented levels of control.

For example, the Nazi regime made deliberate use of mass radio to saturate daily life with centralized propaganda. Under Goebbels, the government promoted the inexpensive Volksempfänger radio receiver to reliably deliver state broadcasts to common households. By controlling the primary communication channel, the regime reduced the space in which dissenting narratives could circulate. Beyond radio, the Nazis also used punch-card tabulating systems supplied by IBM (through its German subsidiary) to process census data. This allowed the regime to act on its ideological priorities with greater speed and consistency, rapidly identifying Jews and other targeted groups.

Other totalitarian governments have made use of similar technologies for various other means of suppressing dissent. For example, in East Germany, the Stasi used an immense archive of files, informant reports, intercepted mail, and wiretaps to anticipate and disrupt dissent before it became organized.

On the other hand, some communication technologies have also been associated with increases in liberty. The spread of print in early modern Europe weakened centralized control over information and helped erode religious and political monopolies. Pamphlets and inexpensive books allowed dissenting ideas to circulate beyond elite circles, contributing to movements such as the Reformation and later democratic revolutions. In some ways, the concept of a written constitution as the foundational bedrock of the United States is contingent on widespread literacy and print culture.

The early internet appeared to have similar decentralizing effects. Digital networks lower the cost of publishing, enabling peer-to-peer communication and reduced reliance on state-controlled broadcasters. During the Arab Spring (~2010-2011), activists in Tunisia and Egypt used platforms like Facebook and Twitter to coordinate protests, share information about state repression, and mobilize large numbers of citizens.

This motivates a natural question: will AI enable more centralized modes of organization, like top-down bureaucracies and totalitarianism, or will it empower more decentralized systems, like markets and civil society?

Structural Mechanisms

Despite the concept of fascism making the “trains run on time”, most historical totalitarian governments were economically dysfunctional, especially compared with their democratic counterparts. In some ways, the entire 20th century can be read as a competition between the relatively decentralized liberal market democracies of the West and relatively centralized totalitarian regimes in Europe and Asia, with the former winning decisively in multiple hot and cold wars, economic growth, cultural production, and technological innovation.

What sort of structural mechanisms explain this pattern? Why did totalitarian regimes underperform democracies, and how might AI change those mechanisms?

We can consider various governments as constrained by their cost-benefit curves. For example, costs of planning, consensus, monitoring, coercion, persuasion, coordination, etc., alter which governance mechanisms are most cost-effective for a given regime. The 20th century favored decentralization because centralization was too expensive, but AI may change many of these costs. For example:

Correlates with authoritarianism:

- Increased centralized information-processing capacity (Hayek and Kantorovich)

- Reduced dependence on broad human labor for wealth generation (Selectorate Theory and the Resource Curse)

- Lower monitoring and enforcement costs (Surveillance at Scale)

- More reliable coercive force with reduced defection risk (Robot Armies)

- Greater narrative control and centralized propaganda capacity (Propaganda)

- Regime coordination advantages over opposition coordination advantages (Coordination Asymmetry)

Anti-correlates with authoritarianism:

- Enhanced distributed information processing (Policy Modeling and Foresight)

- Improved large-coalition aggregation (Consensus Formation)

- Monitoring symmetry between state and citizens (Transparency and Auditability)

- Diffusion of coercive capacity (Civil-Military Diffusion)

- Strengthened informational integrity (Epistemic Defense)

- Enhanced decentralized coordination and innovation (Distributed Innovation)

Let’s explore these speculative mechanisms.

Dictatorship

Hayek and Kantorovich

In Seeing Like a State, James C. Scott argues that a central problem of governance is the ability of a state to see, categorize, and measure the land, population, and capital (the “governants”) under its span of control. The world is complex, so centralized planners use abstract, standardized, and simplified models to monitor the population, allocate resources, and make decisions in lieu of situated, practical knowledge (“metis”). In fact, the state’s desire to understand the system it is managing can in turn alter the system itself, favoring governants with easily parseable and measurable characteristics. Scott calls governants that lend themselves to monitoring and control by a central authority “legible.” Scott goes on to argue that pressure towards legibility (whether successful or unsuccessful) can lead to unintended (often disastrous) consequences.

As an example, consider the Soviet Union’s collectivization of agriculture. The state imposed a rigid structure on farming that ignored local conditions, leading to widespread famine. The legibility of the collective farm system made it easier for the state to extract resources and control the population, but it also made the agricultural system less resilient and more vulnerable to shocks.

Scott’s critique is epistemic. High-modernist schemes largely fail not due to any moral or political issues, but due to failures in the exchange and processing of information. Centralized planners substitute abstract, standardized representations for the dispersed, tacit knowledge embedded in local practice. But all top-down control requires some type of model, and to reject all possible models would be intellectual nihilism. What other option is there? What institutional form can preserve local knowledge while still enabling system-wide coordination?

Along similar lines, Hayek’s famous essay “The Use of Knowledge in Society” argues that the function of economic organization is to aggregate and utilize dispersed knowledge.If a farmer has better insight into the drainage of their field, a shopkeeper knows what items their customers tend to buy, and a factory foreman understands the idiosyncrasies of their particular machinery, then they should each make decisions independently. Instead of top-down control, the decisions are made in a decentralized fashion and markets coordinate their activity via price signals. No one entity needs to understand the whole system.

We can view Scott and Hayek as diagnosing complementary failures of centralized epistemology. Scott emphasizes that administrative legibility suppresses local, adaptive knowledge in favor of simplified representations. Hayek emphasizes that the knowledge required for economic coordination is dispersed, tacit, and constantly evolving, and therefore cannot be centralized in any usable form. Both are ultimately concerned with how large systems originate and process information. The state operates through centralized abstraction; markets operate through distributed adjustment mediated by prices.

The issue is not that a central authority could in principle compute the optimal allocation if only it had more capacity. Rather, the relevant knowledge is generated and updated through decentralized activity itself. Prices function as signals that both transmit and produce information, allowing coordination without requiring any agent to comprehend the entire system.

If markets coordinate via price signals that summarize dispersed information, could a planner simulate those signals? Could optimization theory reconstruct the informational role of prices within a planned system? This ties back to our question about AI and totalitarianism. If AI can originate and process information at a scale and speed that approaches or exceeds human capabilities, it might be able to replace the need for decentralized markets.

This idea has intellectual antecedents. In the 1930s, the Soviet economist Leonid Kantorovich developed the foundations of linear programming while attempting to solve resource allocation problems in a planned economy. He showed that a central planner could in principle use optimization techniques to allocate resources efficiently. However, the computational resources required to solve these problems at the scale of an entire economy were beyond what was available at the time. The Soviet leadership did not adopt Kantorovich’s methods1, and the planned economy continued to struggle with inefficiency and shortages (and ultimately was outcompeted by Western liberal democracies and capitalism).

Nearly 100 years have passed since Kantorovich’s work, and computational resources have increased by many orders of magnitude. The question is whether modern AI could change the relative tradeoffs between centralized and decentralized information processing.

A sufficiently advanced AI system could process real-time sensor data from every factory, farm, and storefront. It could model consumer preferences from behavioral data at a granularity that prices only approximate. It could run counterfactual simulations of supply chain disruptions, weather events, and demand shocks. Would a sufficiently powerful AI planner even need markets? In theory, one could update its model continuously, faster than any price signal propagates through a market.

If we view the Hayekian knowledge problem not as an argument for markets, per se but instead as a hypothesis for authoritarian regimes have historically underperformed democracies, then just the shift in the ratio of information-processing power between central planners and decentralized markets could narrow the gap in economic performance and make dictatorships more viable.

Selectorate Theory and the Resource Curse

In a previous post, we explored the political economy of authoritarian regimes through the lens of selectorate theory (developed by Bruce Bueno de Mesquita, Alastair Smith, Randolph Siverson, and James Morrow).

To review, every leader survives by satisfying a “winning coalition.” In democracies, the coalition is large (the electorate), so leaders must provide public goods. In autocracies, the coalition is small (a few elites, generals, party insiders), so leaders can maintain power through targeted patronage.

The key variable is the size of the winning coalition \(W\) relative to the selectorate \(S\). When \(W/S\) is large, the leader is pushed toward public goods provision. When \(W/S\) is small, the leader can buy loyalty cheaply. The model predicts that small coalitions produce bad governance because the incentive structure rewards it.

Consider the determinants of coalition size. When wealth requires broad human participation, agriculture, manufacturing, services, the leader needs the population to be productive, which means providing education, infrastructure, healthcare. The winning coalition is effectively large because many people’s cooperation is needed2.

On the other hand, when wealth is derived from a concentrated source that does not require broad participation, the coalition shrinks. This is the “resource curse” or “oil curse.” Saudi Arabia does not need its citizens’ labor to generate wealth, it just needs a small number of laborers to operate and control the oil infrastructure. The political system reflects the small selectorate, and leads to concentrated power, limited public goods, and authoritarian governance.

Assuming AI can manage itself, and if AI removes or reduces the value of white-collar laborers, then human citizens are irrelevant to the production function3. The political logic that links national prosperity to broad human welfare no longer functions, and the leaders of America would not need the population to generate wealth. All of the economics would flow to the small set of elites and laborers necessary to operate or control the AI.

Surveillance at Scale

A full-scale surveillance state is a defining feature of totalitarian regimes. The ability to monitor and control the population is essential for suppressing dissent, enforcing conformity, and maintaining power. However, the cost of surveillance has historically limited the ability of governments to achieve comprehensive Orwellian monitoring.

The East Germany Stasi, employed approximately 91,000 full-time staff and maintained a network of roughly 189,000 informal collaborators to surveil a population of 16 million, approximately one agent for every 63 citizens4. This was an unprecedented, but not unlimited, level of surveillance. The Stasi still had to prioritize certain individuals and activities, leaving gaps in their surveillance net for spies and dissidents to exploit.

Software has near-zero marginal costs of replication, and advances in machine learning have made it possible to automate and scale many aspects of surveillance, such as facial recognition, natural language processing, and behavioral pattern analysis. A state combined with powerful AI could potentially monitor every citizen in real time, analyzing their communications, movements, and interactions to identify and suppress dissenter before they could become organized.

In some ways, we can already see the early stages of this in China’s social credit system and AI-augmented surveillance infrastructure, which combine data from various sources, including financial records, social media activity, and public behavior, to assign citizens a “credit score” that can affect their access to services, travel, and even employment. Algorithms analyze this data to identify patterns of behavior that are deemed undesirable by the state.

Robot Armies

If, as Max Weber claims, the state is the entity that controls a monopoly on the use of force, then the relationship between the ruler and the military is a critical factor in the stability of any regime. With a human military, the ruler must maintain the loyalty of the armed forces, which can just as easily overthrow them as defend them. This doesn’t necessarily lead to democracy, but it does create a check on the ruler’s power, since the threat of defection can restrain the ruler’s worst impulses.

Autonomous weapons and robot armies can substantially change this calculus. A robot army could be programmed to follow the command hierarchy of whoever controls its systems, and could even be cryptographically locked to prevent unauthorized use. This would eliminate the risk of military defection, as the robots would have no agency or loyalty beyond their programming.

Historically, even the most ruthless dictator had to consider whether the order to fire on a crowd might be the order that triggers a military mutiny. Robot armies eliminate this consideration.

Propaganda

Historically, human writers, filmmakers, radio hosts, and designers were necessary to produce propaganda. This limited the volume and personalization of propaganda.

In contrast, large language models can generate images and text at near-zero marginal cost. Furthermore, AI can be used to personalize propaganda at scale. Some of the largest and most powerful companies in the world are already using AI to microtarget advertisements to individuals based on their online behavior, preferences, and psychological profiles, which results in modified behavior in the advertisees. The same technology could be used by a state to microtarget propaganda, delivering tailored messages to each citizen that are designed to maximize compliance and minimize dissent.

Coordination Asymmetry

There are open questions as to the ratio between fixed costs and operational costs of frontier AI systems. If the fixed costs (energy, compute, data) are high but the operational costs are low, then there is an asymmetry in coordination advantages. This is unlike the printing press, which could be operated by a small group. The state (or large, centralized corporations) can afford to pay the fixed costs of training and deploying frontier AI systems, while dissidents cannot. This creates a coordination advantage for the state that does not extend to the opposition.

On the other hand, inference is cheap and getting cheaper. Open-weight models are becoming increasingly available. It’s possible this asymmetry may not hold in the long term. Regardless, if the state can maintain a significant lead in AI capabilities, it could use that lead to coordinate its activities more effectively than any opposition group, which would be a significant advantage in maintaining power and suppressing dissent.

Democracy

Policy Modeling and Foresight

Democracies hesitate in part because policy consequences are uncertain and politically contested. Different policies (and the tradeoffs between them) are complex and often poorly understood by voters and legislators alike. This can lead to paralysis, as decision-makers fear making the wrong choice and facing political backlash. Alternatively, voters can be misled by misinformation or adversarial branding, leading them to support for policies that are not in their best interest. Similarly, candidates may have incentives to obfuscate the consequences of their policies, or to make promises that are not credible. Voters may not know which candidate to support, and fall back on heuristics like charisma, identity, or tribal loyalty.

AI-assisted modeling could generate more transparent projections of economic, environmental, and logistical consequences. Counterfactual simulations could be run before legislation is passed. This makes the consequences of policies more salient and less subject to manipulation. Voters could make more informed decisions, and legislators could be held accountable for the outcomes of their policies. The same “legibility” technology that enables totalitarian control could also enable more informed democratic decision-making.

Furthermore, competitive institutions in democracies (opposition parties, free press, independent courts, academic freedom) can function as error-correction mechanisms. These could be internal (related to functioning of a given government) or with respect to the actual value function governments are forced to satisfy (survival). Authoritarian regimes overusing AI may make the planner more powerful but may also ultimately be satisfying less competitive value functions. The fundamental goals and values of a dictator are higher variance than a democratic institution, since a democracy is forced to aggregate many disparate preferences. Where democracies may chase broad welfare, dictators may pursue idiosyncratic goals that reduce the viability of the regime compared to alternatives. The dictator’s personal power may be checked by interstate competitive pressure5.

Consensus Formation

One common criticism of democratic governance is that it is slow and inefficient. Projects are commonly bottlenecked by overly cautious or adversarial parties all-too-eager to employ their veto power. Regulations designed to protect the environment, workers, or consumers delay infrastructure projects. Housing construction is blocked by battles over zoning. Entrepreneurs are stymied by lawsuits and regulatory uncertainty. The legislative process is slow and contentious.

This is a structural problem. As we discussed in the selectorate theory section, democratic governors need to aggregate preferences across a large coalition. Aggregating disparate preferences is inherently difficult, especially as the population grows larger and more varied. The same structure that prevents totalitarian governments from overruling the will of the people also introduces latency.

AI could be employed to make consensus formation more accurate and efficient. Large volumes of public input could be clustered, summarized, and translated into structured objections. AI systems could generate compromise variants that satisfy more stakeholders simultaneously. Rather than eliminating pluralism, AI could lower the transaction cost of agreement.

Civil-Military Diffusion

Autonomous weapons and robot armies removed the risk of military defection. A centralized authority that controls the machines controls the monopoly on force.

On the other hand, if AI-enabled weapons and autonomous systems become widely accessible rather than monopolized by the state, the distribution of coercive capacity may shift. For example, the United States has strong norms around citizen control of weaponry. The Second Amendment is a constitutional guarantee of the right to bear arms, and there is a strong culture of civilian gun ownership. If AI-enabled weapons (like cheap drones) become widely available to civilians or weaker states, it could create a powerful deterrent against authoritarianism and centralization6.

If autonomous systems become widely accessible rather than monopolized by the state, the coercive advantage of centralized authority may erode rather than consolidate. Civilian-owned drones, open-source defense systems, decentralized manufacturing, and cryptographically secure coordination tools could lower the cost of resistance.

Transparency and Auditability

AI systems can generate detailed audit trails and anomaly detection.In authoritarian regimes, this enhances surveillance of citizens. In democracies, it can enhance surveillance of the state by the citizens.

AI-assisted investigative journalism, budget anomaly detection, procurement transparency, and real-time oversight tools could reduce corruption and elite capture. If the state is legible to citizens as much as citizens are legible to the state, then the asymmetry narrows.

Epistemic Defense

Democracies depend on a minimally shared informational baseline in order to deliberate. When information environments fragment, consensus becomes impossible.

AI can amplify propaganda and personalized persuasion. But it could be used to verify provenance of content or surface cross-ideological common ground. The same technology that enables narrative manipulation can be used to defend informational integrity.

Distributed Innovation

Democracies historically outperform in technological frontier competition because they tolerate experimentation, failure, and decentralized initiative. If AI lowers the entry cost of prototyping, simulation, and iteration, then democracies may retain a structural edge even if centralized planning improves.

Conclusion

While democracy has historically outperformed totalitarianism, the question is whether AI will change the underlying selection pressures that led to that outcome. Even a shift in the relative efficiency of centralized versus decentralized information processing could have significant consequences for the viability of different political systems and increase the risk of a new wave of totalitarianism. On the other hand, AI could also empower democratic governance by improving policy modeling, consensus formation, transparency, and distributed innovation7.

The same technology that enables totalitarian control could also enable more informed and effective democratic decision-making. The future is uncertain, but the stakes are high. We should be mindful of the potential risks and benefits of AI for governance, and work to ensure that it is used in ways that promote liberty, justice, and human flourishing.

AI Disclosure

I used AI to help draft this essay from my notes and research various historical examples. I made substantial edits to the structure, content, and wording. I did not use AI to generate any of the ideas or arguments in this essay.

Footnotes

In the late 1930s, Soviet doctrine rejected marginalist price theory. Kantorovich narrowly avoided serious repercussions (in some apocryphal anecdotes, recounted in books like Red Plenty, Kantorovich naively sends a letter to a superior, or even to Stalin himself, only to have his life saved when the letter is intercepted by a mid-level bureaucrat). Kantorovich would ultimately win the 1975 Nobel Prize in Economics for his work.↩︎

One question I have: is America’s superior service economy a cause of its democratic institutions, or a consequence of them? The selectorate logic suggests that the need for broad labor participation in wealth generation creates an incentive for leaders to maintain a large coalition, which in turn incentivizes broad education, public goods provision and democratic institutions (which makes the population more productive and hence richer overall). But it could also be that since the institutions are democratic, this creates an incentive to educate and train the populace that allows more high-end labor. Or it could be a mutually reinforcing feedback loop. Relatedly, America tends to have a strong consumer culture, especially compared to anemic demand in more authoritarian economies, like China. Is this because the wealth in America is more broadly distributed, which creates more demand, which creates more growth, which creates more wealth, which creates more demand? Or does the distribution of wealth and distribution of demand somehow entrench the democratic institutions?↩︎

It’s also possible that AI will increase the returns to high-level white collar work as it acts as a “force multiplier” for human labor. For example, a human programmer could use AI to write code faster and more efficiently, or a human researcher could use AI to analyze data and generate insights more quickly. It could also make education cheaper, which would increase the supply of skilled labor. If AI increases the returns to high-level white collar work, then it could actually increase the need for broad human participation in wealth generation, which would incentivize leaders to maintain a large coalition and democratic institutions.↩︎

Stasi Records Archive (BStU), “Introduction”; Helmut Müller-Enbergs (2010). The 189,000 figure for unofficial collaborators is accepted by the BStU, though some scholars have proposed lower estimates↩︎

This is not to say that democracies are necessarily more likely to survive than dictatorships. This could just lead to races to establish the most efficient dictatorship.↩︎

To be clear, I’m not advocating for citizen control of robot armies. There are many problems with widespread civilian access to powerful weapons, such as increased violence, crime, and instability. It could also create a risk of accidental or intentional misuse.↩︎

Based on this exercise, the arguments in favor of increased dictatorial control seem more numerous and compelling to me than the arguments in favor of increased democratic empowerment.↩︎