Primary Functions

1. Communication, Signalling, and Coordination

In this world, nothing causes true anxiety except death and status. - Procopio

Mediated performances, where an artist encodes and transmits information across mediators to an audience that then decodes it, are by definition a type of communication. So let us start by investigating communication as a social process. What are the evolutionary benefits of communication?

1a. Natural Selection and Communication

Ultimately, natural selection is concerned with persistence. The most “primitive” type of selection is inspection bias: if we inspect a sample from a distribution of objects with variable lifetimes, the sample overrepresents those with longer lifetimes. If this sampling occurs repeatedly, the effect is concentrated.

How does communication enable persistence? One way is via coordination, which enables collective action. Organisms that act collectively may be able to pool resources, specialize, or act more efficiently, enhancing survival. A second way is via replication and persistence of the information itself, outside the original organism. Communication allows adaptive information to persist and accumulate across generations without waiting for genetic encoding7. Otherwise, organisms would have to learn from scratch each generation. Both mechanisms are downstream of communication’s basic function: making one agent’s information available to another.

What kind of information can be transmitted via art? I’d sort these into two categories: “affective” and “ideological”8.

“Affective” or “phenomenal” information describes “what it’s like to be” another agent. In Tolstoy’s 1897 essay, “What is Art”, Tolstoy suggests that the art’s function is primarily to transfer emotional content (pleasant or unpleasant) from the artist to the audience, saying that art begins when one person, with the object of joining another or others to himself in one and the same feeling, expresses that feeling by certain external indications.” Tolstoy goes on to say that art, like speech, “serves as a means of union among [people]”. Similarly, in The Principles of Art (1938) Collingwood argues that art is the clarification and expression of emotion, though he claims that the artist discovers what they feel through the process of creating the art.

One issue with purely affective theories is that artistic creators may engineer in the observer an emotion or a belief that they themselves do not experience or ascribe to, often in an attempt to control the observer or induce a specific behavior. That is, art is not inherently “true”: an artist may lie or behave strategically. Battleship Potemkin (1925), while art, is designed to evoke solidarity with the revolutionaries opposing Tsarist oppression. More innocuously, the creators of movie posters or designers of brand may use emotion as an instrument to incentivize purchases, even if they themselves do not enjoy the product.

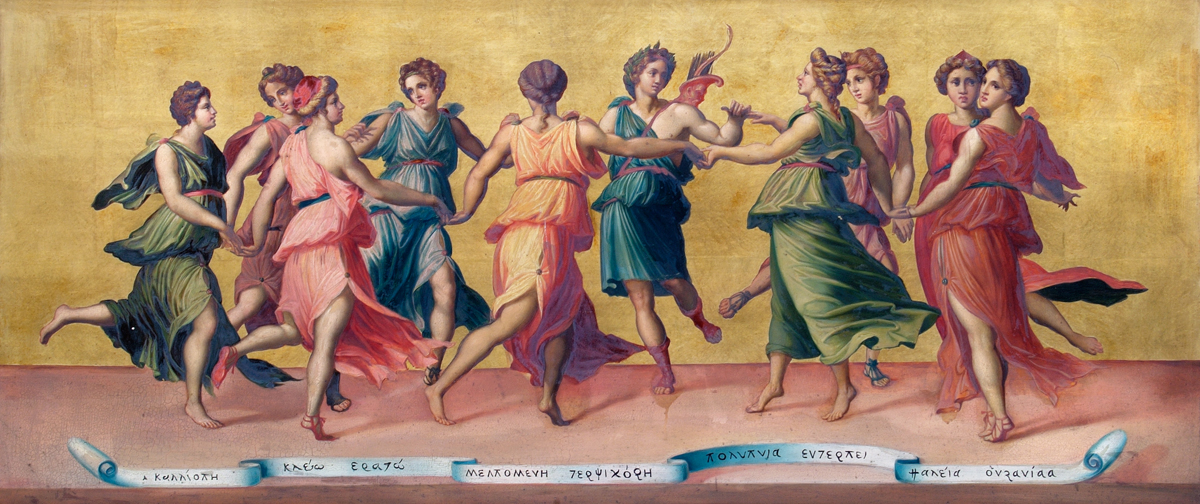

This brings us to ideological art. The goal of some art is not (or is not only) to make the audience feel something, but also to make them believe something. This could be about history, religion, morality, or politics, among others.

Recognition of the power of art to shape belief goes back at least to Plato, who wanted to censor poets. In The Republic (especially Books 3 and 10), Plato argues that poetry’s capacity to implant convictions through vivid imitation (mimesis) make them dangerous. Homer’s epics, for instance, portray gods as petty and immoral, and portray heroes as driven by passion over reason. Plato feared that this would lead listeners to accept flawed models of virtue, justice, or the divine. Similarly, Byzantine or medieval Christian panels were designed not just for devotion but also to convey specific theological doctrines, like the divinity of Christ or the intercession of saints.

Ideological art exploits the communicative link between creator and receiver to transfer convictions, which may be held genuinely by the artist or deployed strategically. Such art feeds into broader social coordination (which we will explore shortly) and aligns entire groups around shared beliefs (as with state propaganda or national epics). This distinguishes it from purely affective art, though the two often intertwine: belief is harder to instill without emotional resonance.

1b. Sexual Selection and Signalling

In Darwin’s 1871 book, The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex, he introduced the concept of sexual selection. Sexual selection favors traits that enhance mating success despite not necessarily favoring survival. In Geoffrey Miller’s book, The Mating Mind (2000), he argues art signals fitness: the capacity to create complex, novel, aesthetically compelling work demonstrates intelligence and creativity. In fact, simply observing that the art is there indicates that the creator had surplus resources to conduct the performance, whether that’s excess energy for a bird to perform a mating dance or excess economic and social capital to produce a film9. The costliness makes the signal more honest, as you can’t spend resources you don’t have10.

A common theory of sexual reproduction is that it’s evolutionary function is to exaggerate genetic variance through genetic recombination, producing more diverse phenotypes. Less remarked upon is that the incentives of sexual selection also favor increased variance: mate choice (on behalf of females) creates pressure to stand out from competitors (on behalf of males), increasing variance11. In fact, as Richard Prum argues in The Evolution of Beauty, runaway selection can produce arbitrary preferences. Aesthetics can be self-reinforcing, and beauty doesn’t have to track useful traits (at least in the short-term).

For example, consider an illustrative example: a population of men and women, where the men vary in penis length and the women vary in penis size preference. Having a larger penis is detrimental to long term fitness, as growing and maintaining a large penis requires additional resources, like energy. However, suppose due to random variation there is a slight preference among the female population (or a subpopulation) for larger penises. This will bias the descendant men to have larger penises, as the large penised men will have a higher probability of reproducing. Since the women with the strongest preferences for large penises will tend to breed with men with larger penises, the women of the largest penised men will tend to have strong preferences for long penises. After many generations, we can expect both long-penis-having and long-penis preserving to increase in the population, perhaps until those characteristics becomes detrimental to fitness12. Many similar examples exist in biology, such as peacock’s tails and bowerbird’s nest construction. Runaway sexual processes are also well-documented in stag beetles (antler size), Irish elk (antler span reaching maladaptive extremes), and numerous bird species.

However, a large penis is not art. Just because a signal is subject to sexual selection is not sufficient to call it “art”. This is why we include “extrabiological” in our conditions for art. However, there are behavioral exceptions as well. For example, many sports can be instrumentally validated13, so they are not art even if used in sexual signalling. Similarly, economic success in and of itself is not art, even if it may be employed to construct sexual signals.

Our example also shows how the act of interpreting a signal is itself part of the sexual selection process. Preferences propagate alongside the relevant trait. By analogy, this also applies to art: appreciating art is itself a signal in the signalling game.

Good taste indicates you can distinguish “good” from “bad” art, which plausibly correlates with intelligence, social awareness, and reasoning ability. And good taste and good art are mutually reinforcing. If we assume “good art” is art with high-fitness meaning (sexual or natural) while “bad art” carries low-fitness, then good taste signals overall mate fitness through the ability to detect the relevant signals well. Good taste shows you can identify true art; choosing true art shows you have good taste.

However, signalling doesn’t occur in a vacuum. Standing out requires differentiation from the local context, not just absolute quality. So a signal’s value depends on the current distribution of current signals. This explains why artistic norms vary across cultures and eras. Art is relative and multidimensional.

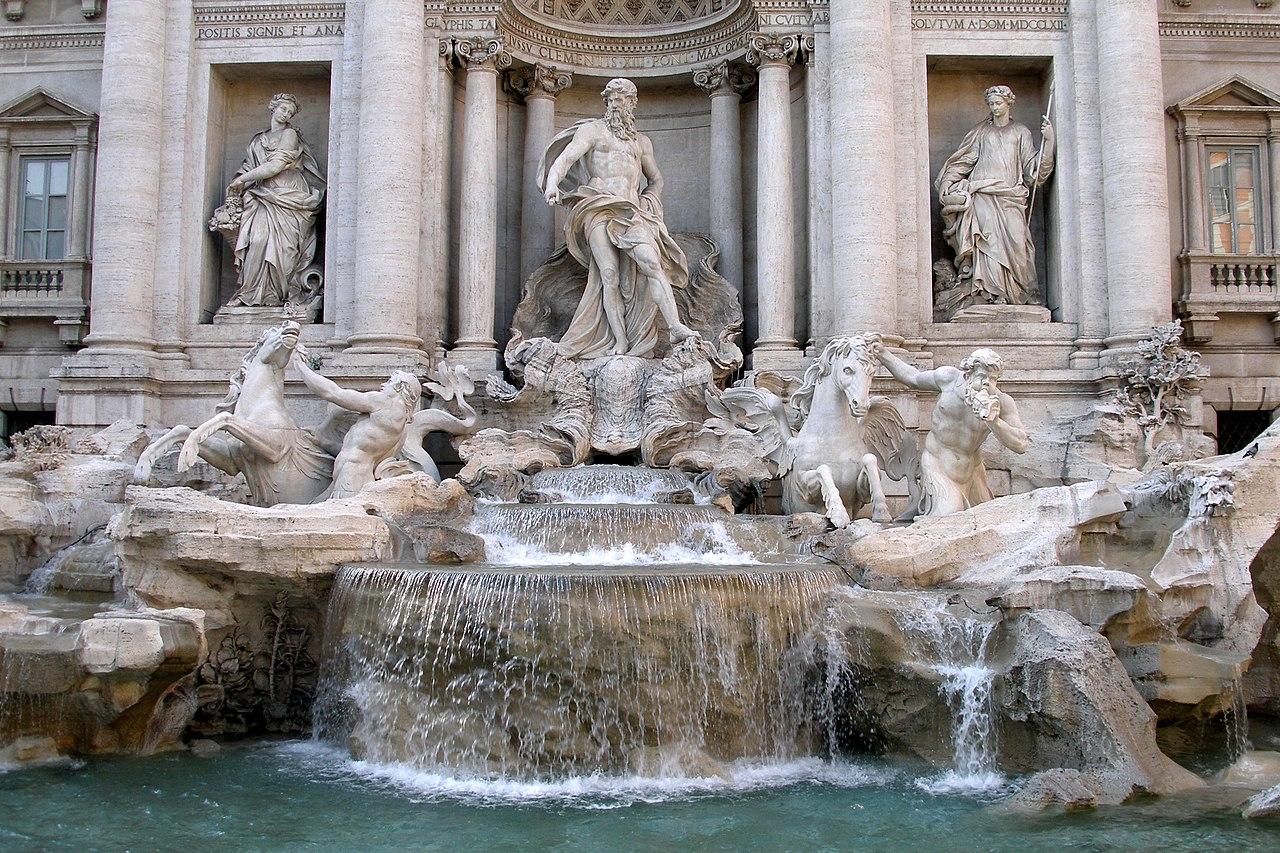

In sexual selection, signalling is typically just to a potential mate or mates. But humans also signal to groups, and groups signal to other groups. For instance, a cathedral signals not just individual piety but also collective wealth, coordination capacity, and devotion. Art can be used as a general social coordination mechanism.

2. Ontological Research

We have played fast and loose with the word “good” in relation to art. But what do we mean by “good”?

In the short run, artistic value is whatever the group converges on. But if value were entirely socially constructed, all art would be equally valid. This is clearly not true, as some artistic ideas survive centuries, while others quickly lost or forgotten. What determines why some information persists in societies, and other information does not?

The answer is that art does something beyond simply coordinating: it encodes “true” information about reality. Even practices with false explicit justifications can persist if they confer adaptive advantage. For example, ritual child sacrifice during famines, however horrifying, can function as population control or signal commitment. For these reasons, groups practicing child sacrifice may outcompete those that don’t, in some sense “justifying” the sacrifice. Similarly, Leni Riefenstahl’s Triumph of the Will was effective at coordination despite leading to heinous outcomes. Groups that coordinate on “useful” information (information that helps the group model the world and cohere socially) persist better than groups that coordinate on less “useful” information. In the long run, cultural selection18 filters for art that tracks “truth”.

“Truth” comes in multiple non-equivalent senses. Ontological truth concerns the world’s actual structure (physical existence, cause-and-effect, invariants) whether or not anyone is there who can articulate that structure. Epistemic truth is about where the specific claims a work advances correspond to reality. Pragmatic truth is about evolutionary utility: a belief or practice is “true” in the sense that it improves persistence, even if the explicit content of the knowledge is epistemically or ontologically false19.

The view that art may represent some “truth” about the world stretches back at least as far as Plato. Plato argued that true reality consists of eternal Forms. He was suspicious of art, claiming that since art was copied from physical objects, which were in turn imperfect copies of Forms, that art was thrice-removed from Truth, thus rendering it a poor form of inquiry.

We previously explored Borges’ metaphor of The Library of Babel. Almost all books are noise, but somewhere in the stacks are “texts” (or other artwork represented as strings) that present genuine truths about reality, predict the future, etc., or at least present them in compressed form.

Why do compressed ideas tend to be beautiful? One answer20 is that beauty is compression. That is, we find things pleasing when they help us compress our model of the world. But in the framing of this essay the causation runs the other way. Compressed ideas are easier to transmit, remember, and coordinate around. A compact formulation spreads faster than a sprawling one. Compression correlates with persistence, and the ideas that persists are the beautiful ones. The aesthetic preference for elegance is downstream of transmission dynamics21.

Regardless, the problem is finding the texts, evaluating them, and ultimately agreeing on them.

Grounding

If long-run selection filters for useful information, how does this filtering actually work? The utility of a belief or practice may not be apparent for generations. A group might coordinate on a harmful idea and not discover the cost until it’s too late.

Several mechanisms help close this gap:

- Proxies

Taste intuitions evolved to track utility without computing it directly. If your ancestors who preferred certain landscapes survived more often, you inherit that preference as a felt sense of beauty.

- Cross-group observation

Groups can observe which other groups thrive and imitate their practices. A canon that persists across multiple independent cultures is more likely to encode genuine truth than one confined to a single group.

- Nested selection

Selection operates across all groups and timescales simultaneously. Within a group, individuals compete for status by predicting future consensus. Across groups, cultural packages compete for adoption. Across generations, biological evolution shapes the taste machinery itself. Faster loops provide feedback to slower ones22.

Over many generations, these mechanisms select for individuals with good taste intuitions and for the preservation of objects and texts those individuals create. Groups also develop meta-taste, such as judgment about which curation mechanisms to trust, which preservation traditions to maintain, which critics to follow (or at the very least, the bad ones are selected out).

Can coordination itself create ontological depth where none existed? Searle argued that collective intentionality creates institutional facts. Perhaps art works similarly: collective acceptance doesn’t just recognize value but instead bootstraps it into existence. The canon becomes real because we treat it as real, and treating it as real makes it function as a coordination device that actually helps the group persist.

There are real, historical examples of art instantiating cultural practices and reorganizing institutions ab initio. For example, Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle contributed to the passage of major U.S. food safety laws in 1906. More recently (and weirdly) the movie Spectre (2015) depicted a Mexico City “Day of the Dead” parade, and the city subsequently created a real parade beginning in 2016. Fiction can seed tradition. Successful works become shared reference points, which shift coordination, which shifts policy and practice.

If aesthetic pleasure is a heuristic for utility, why do we sometimes coordinate on art that makes us depressed, nihilistic, or self-destructive? Does the theory account for art that hacks the pleasure heuristic without providing ontological benefit? I would argue yes. First of all, unpleasant art can still encode ontological truth. Tragedy, horror, and nihilistic fiction may accurately model ideas such as mortality or betrayal. Facing these truths, may be more adaptive than ignoring them. Secondly, consuming difficult art signals differentiation and resilience. If most people avoid confronting hard truths, those who seek them out signal cognitive toughness and independence. Third, some art may genuinely be parasitic. Superstimuli exist in other domains (junk food, pornography, gambling), so it stands to reason there could be “parasitic” art as well.Selection is slow and imperfect, so parasitic art can exist in equilibrium, especially if its harms are diffuse or delayed. Finally, harm may operate at different levels. As we’ve discussed, art that damages individuals may still benefit groups (martyrdom narratives, sacrifice myths), or vice-versa. What looks parasitic from one level may be functional from another.

Search Process

How does new “true” art enter the canon?:

- An artist finds a text outside the current consensus.

- Early adopters recognize it, taking reputational risk by endorsing something unproven.

- If the text spreads and becomes a new coordination point, the early adopters gain status.

- As adoption increases, the signal degrades. “Everyone likes it now” means liking it no longer differentiates you.

- Status-seekers must find new true texts to distinguish themselves.

- Return to step 1.

This is kind of a “high-dimensional” version of the Keynesian beauty contest.

This mechanism explains why avant-garde art is polarizing by design (high variance means high expected status payoff for correct bets), the power of critics and curators (they offload risk onto others while reaping rewards for correct calls), and why AI-generated art feels “cheap” (zero risk taken in production, so low signaling value).

Signals naturally degrade, hence the red queen race of getting “ahead of the curve”, the behavior of hipsters23, etc. Good taste involves predicting future consensus. While it may correlate with other desirable mental properties (openness, political views, etc), it presumably is also high value as it predicts what the group wants now and in the future, which is key to leading a group. Similarly, if taste defines the group in some way, then very poor taste could result in exile (or death). Naturally, the successful artists and tastemakers will rise in status242526.

Agent’s Perspective

From the artist’s perspective, the layers we have considered are all blended together. A creator is simultaneously (a) following a local aesthetic gradient (b) considering the audience (c) placing a reputational wager and sometimes (d) trying to compress something real about the world into transmissible form.

Why Disagreement Persists

If long-run selection filters for useful art, why does taste vary so widely?

A few possible hypotheses. First, division of labor. Groups benefit from having members with heterogeneous taste. Some may favor novelty, while others favor tradition. A group of pure novelty-seekers would lose accumulated wisdom, while a group of pure traditionalists would fail to adapt. Variance in taste is itself adaptive.

Second, usefulness depends on context. Art useful for a warrior caste (glorifying honor, sacrifice, or physical prowess) differs from art useful for a priestly caste (emphasizing contemplation, transcendence, and textual authority). Subgroups within a society may correctly coordinate on different art for different functions. Disagreement across niches is specialization.

Third, ongoing search. The space of possible texts is vast, and which texts are “true” depends on the current situation. Disagreement is part of the exploration mechanism.

Art and Science

Art and science are closer than they appear. Both are collective processes for discovering and coordinating on “true” information. Both operate through institutions that canonize some contributions and forget/ignore others. Both advance through individuals who break existing conventions and (if vindicated) reshape the consensus.

In The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (1962), Thomas Kuhn argued that science doesn’t progress through steady accumulation but instead through “paradigm shifts”: periods of “normal science” punctuated by revolutionary breaks that reorganize the entire field. The same dynamic appears in art.

Most artistic production is competent work within established conventions (“normal art”). Occasionally, someone produces work that violates those conventions in a way that others come to recognize as revelatory rather than merely deviant. If the break succeeds, it becomes the new convention. If it fails, it’s forgotten or dismissed as incompetent.

Crucially, “good art” breaks artistic conventions, not necessarily political or moral ones. Transgression for its own sake (shock value, provocation) is not the same as genuine innovation. The test is whether the break opens new expressive or coordinative possibilities that others can adopt and build on. Duchamp’s urinal was revolutionary not because it was offensive but because it revealed something about the institutional structure of art itself. A merely offensive urinal would have been forgotten.

3. Direct Aesthetic Experience

We have investigated the relationship between social coordination and ontological research. Let us now consider the relation to direct aesthetic experience. Why do we experience “beauty” at all? Why do we enjoy seeing a well-composed image, or discomfort at hearing a dissonant chord?

Some thinkers treat aesthetic experience almost as a type of drug, referring to the experience of art as a “disinterested pleasure” (Kant), an “aesthetic emotion” (Beardsley), or an “intensified experience (Dewey).” Perhaps these reactions could also be extended to to explain the creation of art (although many artists seem to view their art as labor). But why would we have these innate reactions?

Denis Dutton’s The Art Instinct (2009) offers a better answer. In it, he argues that aesthetic pleasure is an evolved heuristic. We find certain landscapes beautiful because the ancestors who preferred such landscapes were more likely to survive. We find symmetrical faces attractive because symmetry correlates with developmental health. We enjoy narrative because tracking social causation was essential for navigating coalition politics. Conversely, our disgust reaction to certain types of art signals long-run evolutionary disadvantage. In this account, aesthetic pleasure and displeasure are compressed, preconscious signals that information is likely to be adaptively useful.

If art is information evaluated through taste rather than direct verification, then taste must track something real, otherwise groups relying on it would be differentially outcompeted. Aesthetic pleasure guides individuals through the coordination game without explicitly computing fitness consequences.

But heuristics are imperfect. Ideas can be beautiful and wrong. Pleasure is only an individual proxy, not a guarantee. This is why the social machines around art and other signals exist.

Aesthetic pleasure is the base layer. Social coordination amplifies and filters this signal, and long-run selection pressure ensures (slowly and imperfectly) that what we find beautiful tends to track what actually helps us persist.